From Phrase to Phrasing

A Classical Perspective

De Muzyk zy er toe bestemd, ons gestadig, op eene streelende wyze, orde voor te houden, in te prenten en tot derzelver liefde meer en meer te ontvonken. (Jacob Wilhelm Lustig – Inleiding tot de Muzykkunde, 1751)

Music is destined to continually, and mellifluously, present us with order, impress it unto us and more and more kindle the love for said order. (translation Jan Willem Nelleke)

Introduction

This paper aims to put phrases at the centre of performance practise, an approach that is, in my opinion, long overdue. The research question on which it is based, ‘What can we learn about musical phrases from period sources?’ is an open question, and therefore this paper will be more like an exploration. I have been studying many treatises, mainly from the Classical period, about composition (concerning topics related to the structure of a phrase) and performance (on how to give shape to a phrase as a performer). By exploring this information in relation to scores, I hope to bring theory and practice together, and raise interesting and maybe unexpected aspects of the subject.

Why is this research necessary at all? Probably no-one will disagree that good phrasing is essential. One could even argue that phrasing almost seems to define musicality: someone may play a score perfectly and precisely but a lack of phrasing will demonstrate without fail that he or she has not ‘understood’ or ‘felt’ the music. Phrasing thus encompasses understanding and feeling, and is therefore not an embellishment but fundamentally at the heart of music.

But where is the problem? We all know how the phrases go, don't we? It is my impression that we often take phrasing for granted; we know, or think we know, where a phrase leads because we feel it, but is that really all there is to it? Surely if phrasing makes music ‘understandable’ it implies that it is an agent in clarifying how music is structured; it is likely that a better understanding of phrase structure will enhance our playing. This is the main reason I chose this subject.

The focus will be on music from the Classical period which I define, rather arbitrarily, as from 1750 to 1800. The dates are not crucial but the style is, with its emphasis on melody and well-balanced structure. These structures were prominent within this time frame but not limited to it; we find them sometimes earlier but definitely later like in present day commercial music. In that sense they are truly ‘classic’.

The Classical period was chosen because this well-organized music seemed a good starting point for looking at fundamental principles in phrases and phrasing; but also because the period is interesting as a meeting point of different performing traditions, on modern and period instruments. Though trained on the modern piano, I have experience on period instruments as well and I have found the difference in approach intriguing. It has forced me to reconsider musical certainties and has triggered an interest in basic concepts in a historical context, hence the choice for period sources.

Some further clarifications: I am not a music theorist. I have had the basic training of any professional musician but I have no special qualification. I am a performer doing research to inspire and inform performance and teaching; for music theory specialists my discussion of the theoretical aspects might be too basic.

The show cases and examples other than from treatises, are chosen from compositions I encounter in my capacity as pianist, coach and accompanist. The gamut is therefore limited but the principals behind it not.

Conventions

Words like phrase, period, sentence, etc. have both a general and a musical meaning. But even in a specifically musical context these terms are not unequivocally defined. I will use these words according to eighteenth-century practice with a strong relation to punctuation in language. I want to emphasize that I do not use these terms as defined in later times by for example Arnold Schoenberg; therefore a period does not necessarily have an antecedent-consequent form, and to prevent confusion I will completely avoid the use of sentence as a musical term.

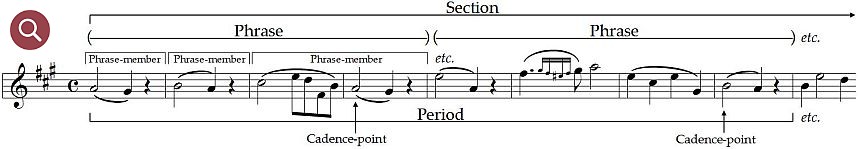

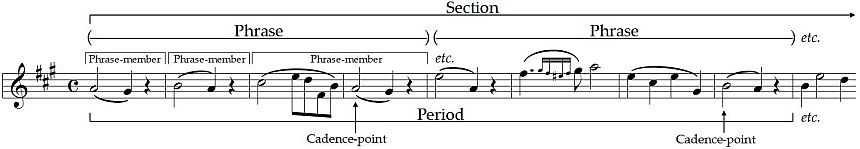

The following terms and definitions will be used, see also Fig. 1 (after an example by A. Reicha1Anton Reicha, Traité de haute composition musicale, Czerny edition, 4 vols (Vienna, 1824), ii, 351.):

- Phrase

- The shortest passage of music that expresses a more or less complete thought.

- Phrase-member

- A part of a phrase, an idea that needs to be elaborated.

- Period

- A group of phrases that reaches a conclusion.

- Section

- A main part of a movement, usually formed by a group of periods except in shorter pieces.

- Phrase-length

- The length of a phrase as related to the number of bars (4 in the example).

- Phrase-rhythm

- A higher level of rhythm created by alternation of phrase-lengths (4 + 4 in the example).

- Cadence-point

- The beat where the phrase wants to land (not necessarily the last note of a phrase).

Figure 1: Terminology.

These terms and definitions have been chosen in an attempt to translate and correlate treatises from different authors. There is an abundance of words for identical concepts and, confusingly, the same word can mean different things with different authors. Appendix 1 contains a list of terms I have encountered during my research, categorised according to the terminology used here.

Unless stated otherwise, all translations are mine.

Unless indicated otherwise, all modernised type-setting of musical examples is mine, with occasional additions or clarifications in square brackets [ ].

© Jan Willem Nelleke, London, 2017